Investigative Classics is a weekly feature on noteworthy past examples of the reporting craft.

Walter Duranty was hardly the only Soviet apologist working for American newspapers during the 1920s and 30s -- an earlier, remarkable period of Russian disinformation in the West. But Duranty has become the most infamous sophist because of his perch, the New York Times, and his acclaim: He was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting in 1932. The Times later called his work "some of the worst reporting to appear in this newspaper" – especially work after he won his Pulitzer (like his articles quoted here).

While it’s well-known that the British-born Duranty denied Soviet-created famine and mass starvation, largely forgotten is the work of another, far more courageous and capable writer.

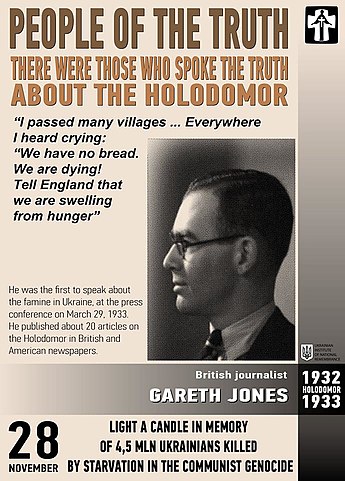

Gareth Jones was a Welshman who made three trips to the Soviet Union between 1930 and 1933, and reported on what he had witnessed for various publications. The experience transformed him:

The internationalism of the Bolsheviks impressed me. They set aside all petty prejudices between races. They abhorred pogrom. They gave rights to the smaller nations to speak their own languages. They were not guilty of the narrow nationalisms of post-war days.

Then I went to Russia.

There I had every chance to see the real situation, for I traveled alone, walked through villages and towns, and slept in peasant homes.

His most famous passage appeared in a widely circulated story dated March 29, 1933:

I walked along through villages and twelve collective farms. Everywhere was the cry, 'There is no bread. We are dying.' This cry came from every part of Russia, from the Volga, Siberia, White Russia, the North Caucasus, and Central Asia. I tramped through the black earth region because that was once the richest farmland in Russia and because the correspondents have been forbidden to go there to see for themselves what is happening.

In the train a Communist denied to me that there was a famine. I flung a crust of bread which I had been eating from my own supply into a spittoon. A peasant fellow-passenger fished it out and ravenously ate it. I threw an orange peel into the spittoon and the peasant again grabbed it and devoured it. The Communist subsided. I stayed overnight in a village where there used to be 200 oxen and where there now are six. The peasants were eating the cattle fodder and had only a month's supply left. They told me that many had already died of hunger. Two soldiers came to arrest a thief. They warned me against travel by night, as there were too many 'starving' desperate men.

'We are waiting for death' was my welcome, but ‘See, we still, have our cattle fodder. Go farther south. There they have nothing. Many houses are empty of people already dead,' they cried.

Two days later, recently minted Pulitzer laureate Duranty published a rebuttal in the Times with the now grimly comical headline: “Russians Hungry, But Not Starving.” He wrote:

In the middle of the diplomatic duel between Great Britain and the Soviet Union … there appears from a British source a big scare story in the American press about famine in the Soviet Union, with "thousands already dead and millions menaced by death from starvation."

Jones did not back down, reporting on April 11, 1933:

There is first the rapid way in which the standard of living has fallen; 1930 was a bad year, but now it seems even prosperous compared with the spring of 1933. Famine stalks the land. Surely the building of vast factories is no compensation for hunger.

There is the savage class warfare, which is no literary slogan, but a real programme of terror.

Class warfare has led to the crushing of millions of innocent people whose only sin was that they were not of working class parentage. It has led to domination by the Ogpu and to visitations of torture.

It has led to justice, which should be above class, becoming a weapon of the Communist Party to crush those who are not of working-class origin. “Art is a weapon of class warfare” was the notice over an art gallery in Moscow. Every thing is subordinated to class warfare. The oppression of religion, which is no myth but a definite fact, is another black mark to be put against the Soviet régime.

Hypocrisy has been bred to a greater extent than ever. Communists dare not criticise the policy of the party, and, though they know that famine is there and that the Five Year Plan has wrecked the country, they still speak of its glorious achievement and of the way in which they have raised the standard of living. But the idealism of 1930 and 1931 has disappeared.

Fear has become the dominant motive of action. The party member fears that he will be turned out of the party. The peasant fears that he will die of hunger. The worker fears that he will lose his bread card. The professor fears that he will be accused of counter-revolutionary propaganda in his lectures. The town dweller fears that he will be refused a passport. The engineer fears that he will be accused of sabotage.

But the greatest crime of which the Soviet régime is guilty is the destruction of the peasantry. Six or seven millions of the better-off peasants have been sent away from their homes to exile. The treatment of the other peasants is has been equally cruel. Their land and livestock taken away from them, they have been condemned to the status of landless serfs.

Duranty, presumably, was unimpressed. That August he told readers:

Any report of a famine in Russia is today an exaggeration or malignant propaganda. The food shortage which has affected the whole population in the last year and particularly in the grain-producing provinces – that is, the Ukraine, North Caucasus, the Lower Volga – has, however, caused heavy loss of life.

The Times commissioned a scholarly investigation of Duranty’s work seven decades later, but the Pulitzer board's administrator declined to revoke the Timesman's prize, citing no clear evidence of deception in the specific articles submitted for the award – even though the paper’s publisher, Arthur O. Sulzberger Jr., condemned his work.

As for Jones, he was captured and shot by bandits in China under mysterious circumstances in 1935 on the eve of his 30th birthday. Suspicion fell on the NKVD, vengeful KGB predecessor under Stalin (above, with Nikolai Bukharin, who clashed with the dictator on collectivization and was executed).

Suffice it to say that Gareth Jones won no such prize as Duranty’s.