Investigative Classics is a weekly feature on noteworthy past examples of the reporting craft.

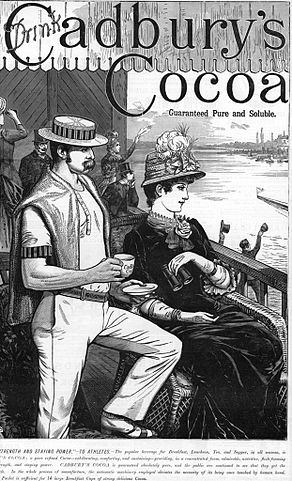

Cadbury ad, 1885 (Wikipedia)

Cadbury ad, 1885 (Wikipedia)Slavery continued long after most Western nations banned it in the early to mid-19th century. A prime location was the islands of San Thomé (now São Tomé) and Principe, off the eastern coast of equatorial Africa, which were major suppliers of the cocoa (beans, above) used to make chocolate treats.

In 1905, the crusading British journalist Henry Woodd Nevinson traveled to the region and reported a six-part series for Harper’s. He traced this modern-day slave trade, in which human beings were shipped from Portuguese-controlled Angola to the islands, where they usually were worked to death.

Nevinson described the brutality of these plantations in many ways, including through the use of numbers:

The official returns of 1900 put the population of San Thomé at 37,776, including 19,211 serviçaes, or slaves, with an import of 4572 serviçaes in 1901. And the population of Principe was given as 4327: including 3175 serviçaes. But the prosperity of the islands is increasing with such rapidity that these numbers have now been probably far surpassed. … . On one of the largest and best-managed plantations of San Thomé the superintendent admits a children’s death-rate of 25 per cent., or one-quarter of all the children, every year. Our latest consular reports do not give a complete return of the death-rate for San Thomé, but on Principe 867 slaves died during 1901 (491 males and 376 females), which gives a total death-rate of 20.67 per cent. per annum. In other words, you may calculate that among the slaves on Principe one in every five will be dead by the end of the year.

His final installment in the series, “The Islands of Doom,” includes a description of the empty laws passed by colonial powers to make slavery not seem like slavery. The enslaved people, for example, were paid small wages, much of which were withheld, and they signed contracts. Nevinson reported:

According to the law, the wages of all slaves must be raised 10 per cent if they agree to renew their contract for a second term of five years. With the best will in the world, it would be almost impossible to carry out this provision, for no slave ever does agree to renew his contract. His wishes in the matter are no more consulted than a blind horse’s in a coal-pit. The owner or agent of the plantation waits till the five years of about fifty of his slaves have expired. Then he sends for the Curador from San Thomé, and lines up the fifty in front of him. In the presence of two witnesses and his secretary the Curador solemnly announces to the slaves that the term of their contract is up and the contract is renewed for five years more. The slaves are then dismissed and another scene in the cruel farce of contracted labor is over. One of the planters told me that he thought some of his slaves counted the years for the first five, but never afterward.

Nevinson’s vivid prose conveys the region’s beauty:

As we climbed into the mountains we looked down into unpenetrated glades, where parrots, monkeys, and civet-cats are the chief inhabitants. The sides of the road were thickly covered with moss and fern, and the high rocks and tree-tops were from time to time concealed by the soaking white mist which the people for some strange reason call “flying-fish milk.”

His writing also captures an almost matter-of-fact cruelty:

Flogging, however, is common if not universal, and so are certain forms of vice. The prettiest girls are chosen by the agents and gangers as their concubines–that is natural. But it was worse when a planter pointed me out a little boy and girl of about seven or eight, and boasted that like most of the children they were already instructed in acts of bestiality, the contemplation of which seemed to give him a pleasing amusement amid the brutalizing tedium of a planter’s life.

Nevinson’s series led to several reforms. Most notably, in 1909, Cadbury Brothers announced that it would no longer buy cocoa from the islands. In 1913, the Portuguese ended the slave trade form Angola.

Still, perhaps reflecting the limits of even the best journalism, African cocoa farming remains controversial, especially for its use of child laborers.