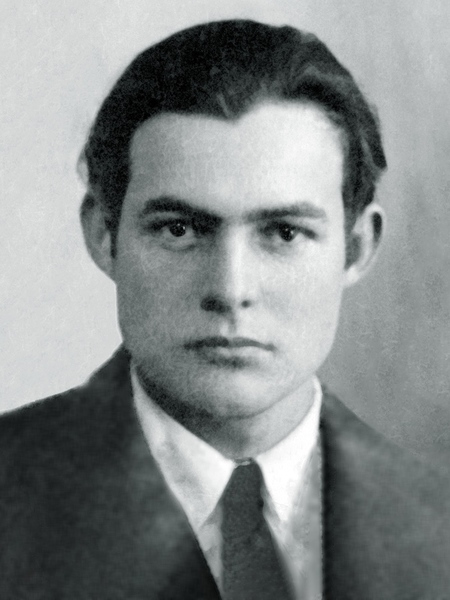

Investigative Classics: Ernest Hemingway's Reporting on Bootleggers, 1920

Investigative Classics is a weekly feature on noteworthy past examples of the reporting craft.

Ernest Hemingway said: “Newspaper work will not harm a young writer and could help him if he gets out of it in time.”

Although Hemingway committed journalism until his death in 1961, he got out of the full-time racket after five years – a brief stint at the Kansas City Star, where he never earned a byline, followed by a far more productive four years working for the Toronto Star (1920-24).

The Canadian paper has assembled an absorbing archive of Hemingway’s dispatches – from Toronto, the US and Europe – as well as some insightful articles about how journalism influenced his famously lean, muscular prose style. Reporting provided him entrée, to famous people and notable events, that would shape his fiction. He covered bull fights, criminals and fishermen before he immortalized them.

Because he is, well Hemingway, it is hard to decide whether so much of this century-old work seems so fresh because of its punchy style or because of the author’s fame. Here’s a scene from a story about Prohibition-era liquor smuggling:

On the train from Toronto to Windsor, I talked with a man who was bringing twenty cases of whiskey to Windsor. He estimated that his profits on the liquor when it was deposited on the United States side would be fourteen hundred and fifty dollars.

“It’s a little risk,” he said. “We run it all at night in small boats. The revenue agents have motorboat patrols, but we keep out of their way pretty well.”

According to this bootlegger the recent story about the electrical torpedo which was said to be shot from Canada to the United States filled with liquor is a pipe dream of some overworked newspaperman. “It is either a straight newspaper fake or else the revenue men started this yarn,” declared this man, who ought to know. “There is so much booze coming into Detroit that the revenue gang have to have an alibi somewhere, so they may have framed the torpedo story.”

Here’s how he opened a story about the murder of an underworld figure in Chicago:

Anthony D’Andrea, pale and spectacled, defeated candidate for alderman in the 19th Ward, Chicago, stepped out of the closed car in front of his residence and, holding an automatic pistol in his hand, backed gingerly up the steps.

Reaching back with his left hand to press the door bell, he was blinded by two red jets of flame from the window of the next apartment, heard a terrific roar and felt himself clouted sickeningly in the body with the shock of the slugs from the sawed-off shotgun.

It was the end of the trail that had started with a white-faced boy studying for the priesthood in a little Sicilian town. It was the end of a trail that had wound from the sunlit hills of Sicily across the sea and into the homes of Chicago’s nouveau riche. A trail that led through the penitentiary and out into the deadliest political fight Chicago has ever known.

Amazing to think that after enjoying such prose, many readers used the pages to wrap their fish and line their bird cages.