The panic and outrage were palpable last February when President Trump announced plans to trim reimbursement rates for government-funded scientific research.

“This is going to decimate U.S. scientific biomedical research,” Northwestern University biologist Carole Labonne told Bloomberg. “The lights will go out, people will be let go, and these [medical] advances will not occur,” David Skorton, CEO of the Association of American Medical Colleges, told PBS. “The goal,” University of Washington biologist Carl Bergstrom warned on BlueSky, “is to destroy U.S. universities.”

The sky has not fallen on American research in the 10 months since. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is still paying the same 50% to 70% in indirect costs – the premium added on top of grants meant to reimburse universities for providing labs and other research infrastructure – because lawsuits have frozen the president’s proposed policy. One Trump official admits this is unlikely to change because the administration will almost certainly lose in court. The current system, which provides the lion’s share of billions of dollars each year for often-unspecified overhead costs to universities, has the backing of Congress. As it stands, there appears to be no momentum, even among Republicans, to reform the practice.

“It’s basically a slush fund,” one NIH official told RealClearInvestigations. “We just don’t like to call it that.”

A RealClearInvestigations analysis of these indirect payments reveals a long, largely forgotten history of concern about taxpayer-sponsored research. Although many researchers have cast Trump’s proposal as an attack on science, this issue isn’t the need to fund research activities that sometimes lead to beneficial discoveries, but whether some of the billions that support the necessary infrastructure and equipment are actually being shifted to purposes such as staffing and buildings that have little or no direct connection to the actual research.

In the late ’80s, Stanford faculty revolted against the university’s high overhead charges for diverting research dollars to a bloated administration and a campus building frenzy. Those concerns are still voiced by some.

“If the universities truly believe that it takes 60-70% of a research grant to provide facilities, utilities, and other basic support, then that is easy to prove by opening the books,” said Sanjay Dhall, a research physician at the University of California, Los Angeles. “I suspect however, that opening the books would reveal that a significant chunk of these funds, or even the majority, are paying an army of unnecessary administrators.”

At a time when the value of college is being challenged because of exorbitant tuition and fees, and the federal government is struggling to rein in debt, the story of indirect funding offers a window into the history of runaway costs and the growing power of college officials. RCI has also learned that NIH Director Jay Bhattacharya has been selling a new plan that makes the grant process more competitive for institutions that were overlooked in the past.

Indirect Costs Hard To Define

Distributing over $37 billion in grants every year, NIH is the largest funder of biomedical research on the planet, far exceeding the European Commission, which spends around $12 billion, and dwarfing the Gates Foundation’s $1 billion.

Every NIH grant a university researcher receives provides two categories of funding: direct and indirect costs. The direct costs include all items the researcher submitted as part of the project’s budget, from laboratory equipment to a percentage of salaries.

Indirect costs are harder to define. The funding goes to administrators, and how they use it is shrouded in mystery. What’s more, indirect rates vary from university to university for reasons that few understand and can explain.

While institutions charge private foundations like Gates a mere 10% and Rockefeller 15% for indirect costs, they charge the NIH much higher rates – 69% for Harvard, 67.5% for Yale, and 63.7% for Johns Hopkins.

“How do you think Harvard built all those buildings?” one NIH official, a graduate of Harvard Medical School who insisted on anonymity, told RCI. “NIH indirect costs paid for that.”

When Trump first proposed the 15% cap in 2016, Harvard president Drew G. Faust told the student newspaper in late 2017 that she flew to Washington, D.C., to lobby Republicans in both the House and the Senate to stop it. “We’re bringing in quite a bit of money through federal contracts which provide money for a lot of buildings and other infrastructure that makes possible what we do going forward,” a Harvard dean told the student newspaper. “So if that was to all go away, we’d have to sit down and look at that.”

The Trump administration’s proposal to cap overhead at 15% would cost university administrators billions of dollars that they control. Among the many critics was Holden Thorp, editor-in-chief of the flagship journal Science and a former university administrator. He wrote an editorial last February titled “A Direct Hit” that described the cap as a “ruthless takedown of academia.”

“The scientific community must unite in speaking out against this betrayal of a partnership that has enabled American innovation and progress,” he wrote.

In response to questions from RCI, Thorp said any change to NIH overhead funding should be done in partnership with the scientific community. “Indirect costs are used to secure debt on research facilities and were treated as very secure by banks and the rating agencies,” Thorp said. “Pulling all of that abruptly – without following processes with decades of precedent – is certainly betraying a partnership by putting the universities in difficulty with their lenders and bond ratings.”

Inexorable Rise in Charges

It turns out that concerns over universities possibly misusing federal grant money date back more than half a century, according to Thorp’s own publication. In 1955, the federal government almost doubled the 8% premium paid for university overhead. A decade later, Science reported that Congress lifted the overhead ceiling to 20%, maintaining a flat rate to assure more taxpayer dollars were targeted at scientific research, and less spent on constructing new buildings. Some members of Congress believed that “the universities need not accept the grants if they can’t afford them.” Elected officials also worried that indirect costs would not go to research but to support other university efforts.

“You might be surprised if you read the list of money being spent for research in various universities,” one senator said in a 1963 Science news story. “Not only to pay the teachers, but also to construct buildings and facilities around the school.”

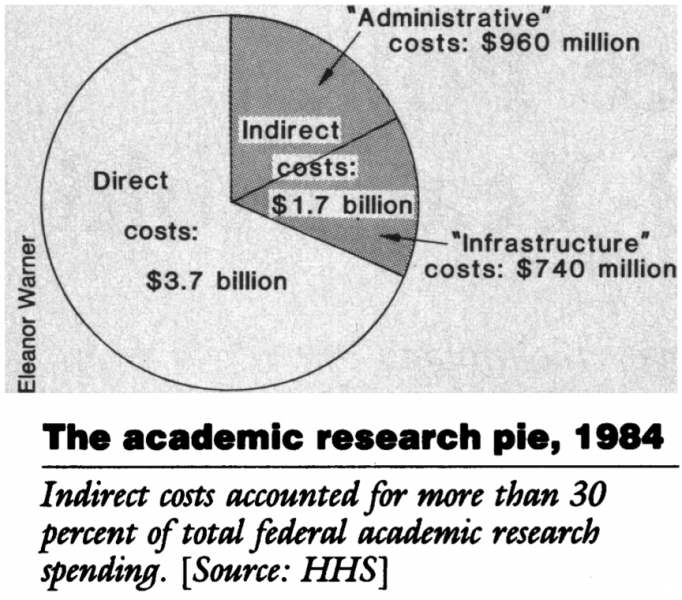

Despite these concerns, lobbyists convinced the government in 1966 to remove all caps, empowering universities to negotiate directly with federal agencies to set their own overhead rates. In 1966, overhead consumed 14% of NIH grant expenditures. By the late 1970s, it consumed 36.4%. When the federal government attempted to backpedal in 1976 to bring “spiraling indirect cost rates under control,” it failed.

Both Republicans and Democrats have long championed increasing NIH budgets, partly because grants for research land in congressional districts scattered across the nation. Republicans have often been the NIH’s biggest supporters. Fifteen years ago, Congress launched investigations into the NIH’s poor monitoring of grants that were awarded to research physicians with undisclosed ties to the pharmaceutical industry. Despite the unfolding scandal, Republican Sen. Arlen Specter pushed through a 34% increase in the NIH’s budget in 2009. During the 2013 government shutdown, the NIH was one of the few agencies that Republicans pushed President Obama to keep open. Two years later, Republicans cut many parts of Obama’s proposed 2015 budget, yet gave the president even more money than the increase he requested for the NIH.

Like some elected officials, academics have also long complained that high overhead harms academic scientists by diverting NIH funding to administrators. In 1981, a University of California researcher published a study in Science, which showed how “Funding has thus been markedly reduced, and this has become a critical factor limiting research support in the United States.”

By 1983, indirect costs accounted for 43% of the NIH grant budget. In response, then-NIH Director James B. Wyngaarden pushed to make more money available for scientists by paying administrators only 90% of what they claimed in overhead.

“[L]egislators tend to sympathize with the investigators who are more interested in seeing federal money spent for equipment and researchers’ salaries in their labs than for light and heat and the services of typists and bookkeepers,” reported Science at the time.

However, Science reported that Wyngaarden was met with stiff opposition from university officials and their allies in Congress.

When Wyngaarden tried to deal with the matter by sending a report to Congress, Science reported, officials from several university lobby groups shut the report down, calling it not “acceptable.”

One of Wyngaarden’s biggest critics was Stanford President Donald Kennedy, whose school was then charging one of the highest rates for indirect costs. Kennedy convened a group to attack cost-saving proposals, stating in a letter, “The NIH proposals to reduce reimbursement of those costs … will directly damage the research effort as a whole.”

This effort appeared to succeed until Kennedy himself became ensnared in a scandal that showed Stanford’s indirect costs charged to the NIH paid for a bevy of personal goods and upkeep on a yacht.

Stanford’s Taxpayer-Funded Yacht

Stanford’s yacht, the Victoria, was valued at $1.2 million and became a symbol of excess, with walnut and cherry paneling, brass lamps, marble counters, and lavish woodwork. Administrators used the yacht as a fundraising venue to wine and dine campus bigwigs. NIH money had paid for overhead to maintain it.

As Congress and federal investigators dug into Stanford’s accounting, they discovered that administrators had also redirected NIH research overhead to pay $2,000 a month for flowers at President Kennedy’s home, $7,000 for his bed linens, and $6,000 to provide him with cedar-lined closets. Another college official had hosted Stanford football parties and charged the NIH $1,500 for booze.

Humiliated in the media, Stanford was forced to lower the indirect rate it charged the NIH from 78% to 55.5%, and federal agencies launched audits of overhead charges at dozens of other universities, resulting in millions of dollars returned to the NIH.

With the politics and the media on his side, Michigan Congressman John Dingell launched reforms to indirect charges. Stanford and other institutions were forced to halt expensive building campaigns. President Clinton proposed a cap on indirect costs in a “concerted effort to shift national spending from overhead to funding research.” As in the past, universities opposed the change, and the White House buckled.

“One way or another, I’ve been involved in controversy about indirect cost rates for about 30 years,” a chancellor at the University of Maryland told The Baltimore Sun in 1994.

Kennedy resigned from the Stanford presidency, as did several of his administrators. Kennedy later joined Science as editor-in-chief – a predecessor to Thorp – while universities’ charges for indirect costs to the NIH eventually snapped back to their former pricing, which continues to this day.

RCI spoke with several academic researchers at institutions scattered across the U.S., working at both private and public-funded universities. None wished to be named about their concerns about how their administrators spend NIH indirect funding, with one professor noting that administrators determine your career, so it makes no sense to criticize their spending habits.

While university presidents say administrators strictly account for NIH indirect funds, the reality appears to be different. Professors who bring in large sums of NIH money, sometimes referred to as heavy hitters, can complain and get some of the indirect costs back from the administrators for their own research and even personal use. At some institutions, department heads can get a cut of the indirect costs to set up slush funds, monies they can dole out to favored professors, or even divert to their own labs.

Professor Dhall said that after he published a March letter in the Wall Street Journal that supported Trump’s cap on indirect rates, he was contacted by colleagues across the country. “They congratulated me on going public and vehemently agreed, in private,” he said.

A congressional staffer who has spent decades investigating problems at the NIH said that nobody truly understands how universities negotiate their NIH overhead rates. And once that money gets to the university, it disappears into a byzantine accounting system that seems designed to confuse government auditors, who rarely inspect university books.

“It’s a complete black box,” he said. “I wish someone could explain it to me.”

Trump’s Play To Change the Game

The Trump administration will lose the fight to cap indirect costs at 15%, a senior HHS official told RCI, because of the universities’ outsize influence. During the first Trump administration, universities caught wind that Trump planned to cap overhead rates. As they had done for over half a century, university lobbyists ran to Congress to complain, only now they sought an alliance with the pharmaceutical industry.

Responding to lobbying pressure, Republicans in the House and Senate inserted a provision into the appropriations bill in 2018 to block Trump’s attempt to change universities’ indirect cost rates. That provision has been included in every succeeding appropriations bill.

While it does not seem likely that Congress will strip the schools in their states and districts of billions of dollars in funding, NIH Director Bhattacharya has been floating his own proposal to revamp indirect payments to make them more equitable in private talks with members of Congress and university leaders. Shortly before Thanksgiving, Bhattacharya gave a dinner talk to the Republican Main Street Caucus, a group of 85 GOP members of Congress who are critical behind-the-scenes players among Republicans now running the House.

A dinner participant recounted to RCI that Bhattacharya noted that more than half of the NIH’s money goes to 20 universities located on both coasts. These elite universities win a lion’s share of the grant money, including indirect costs, because they have the money to attract excellent scientists, in part because NIH money helped them build great infrastructure.

This creates a vicious cycle that guarantees NIH will continue to fund institutions that have already won past NIH money – and which charge high indirect costs. To end this cycle, Bhattacharya wants to break off indirect costs into a separate category of infrastructure grants that universities can compete to win.

During the talk, Bhattacharya said that all the universities in the entire state of Florida now get as much money as Stanford. Yet, there’s no reason Florida could not become a hub for scientific research if the federal government invested in its scientific infrastructure.

If Florida can provide lab space at a lower cost than Stanford, he said, they should get the money. Bhattacharya also wants to make it easier for academics to take their grant to different universities. If a Harvard researcher is offered more space or better facilities at a university in Kansas, because building costs there are cheaper, that professor should be able to transfer his grant.

The NIH already provides specific grants for infrastructure, and the hope is that spreading the billions in indirect costs across the country will gain political support.

“He wants to get this money out to the middle of the country, not just the coasts,” said Congresswoman Mariannette Miller-Meeks, Republican from Iowa. Dr. Miller-Meeks is one of the few physicians in Congress and said she was impressed with Bhattacharya’s talk at the Main Street Caucus dinner. However, she is uncertain whether Democrats would embrace the new proposal in today’s polarized environment.

“I would think there are members from the center of the country that would like to see more money in their district,” she said.

A spokesperson told RCI that NIH remains focused on ensuring that funding is used efficiently and that direct and indirect costs contribute to scientific productivity. “Bhattacharya’s proposal represents one of several ideas being discussed publicly about how to structure federal support for research infrastructure,” the spokesperson said. “NIH looks forward to continuing to work constructively with Congress on this issue.”