More than a million Americans may unwittingly hold second jobs – because that work is being performed by an illegal alien using their stolen social security number.

News of the identity theft can come as a rude shock to citizens like the Minnesota factory worker who had crushing tax bills because of a thrice-deported illegal immigrant in Missouri who was working under his name for years. Or Iowa taxpayers who learned that the superintendent of the Des Moines school system was an illegal immigrant facing a deportation order.

More likely, they may never know that their identity was pilfered, perhaps by one of the 70 illegal workers accused last summer of stealing more than 100 identities so they could work at a Nebraska meatpacking plant, or by one of the 18 individuals charged with “aggravated identity theft, misuse of Social Security numbers, and false statements” in March.

While the crimes may seem innocuous or something committed more in cyberspace than in everyday life, they are far from victimless law-breaking. Studies show that identity theft can often lead not just to financial pressures, but also emotional and physical stress.

“There are real victims involved in this. When someone gets your or your child’s Social Security number, that is no longer a victimless crime,” said Ron Mortensen, a retired Foreign Service Officer and former human resources director with the 2002 Winter Olympics in Utah.

A RealClearInvestigations analysis has found that the federal and state governments bear some responsibility for this harm to American citizens because of their failure to address long-acknowledged weaknesses in the primary tool used to limit this identity theft – E-Verify.

Established in 1997, the federal E-Verify system allows employers to establish whether the information applicants provide on their Form I-9 is valid. It is not infallible – it confirms information by checking it against various federal records, but doesn’t confirm if that information belongs to the applicants. Still, most experts consider it an effective deterrent.

“E-Verify isn’t foolproof, but it’s actually pretty good for a government program,” according to Mark Kirkorian, the executive director of the Center for Immigration Studies. “It doesn’t screen a large part of the illegal immigrants in the country, but you have to commit a felony to fool it.”

Nevertheless, while it is mandatory for those working on federal projects or contracts, only nine states also require its use for all larger private employers, according to I-9 Intelligence, an E-Verify compliance company. In most other states, the system, administered by the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), a branch of the Department of Homeland Security, is voluntary. California actively restricts its use; Illinois discourages it.

Although it is against the law to employ those who are ineligible to work in the U.S., the fines are relatively modest, rising to criminal charges only with repeated violations. Consequently, the net that E-Verify might throw over the illegal immigrants seeking employment has rips. In the Iowa incident, the head of the Des Moines school board told the New York Times that it does not use E-Verify to check applicants’ work eligibility.

From time to time, a bill has been floated in Congress – most recently by Iowa Republican Sen. Chuck Grassley – to mandate E-Verify, but none have approached the 60 Senate votes necessary to pass. Mortensen believes E-Verify could be implemented via an executive order, but acknowledged that, like virtually all steps taken by President Trump, it would be sure to face a legal challenge.

It is unclear how effective that move would be, as there are hiccups in the system. As of Tuesday morning, the government’s E-Verify website was full of broken links regarding “Hiring Sites, FY2025 Cases, and Usage past 365 days by state.”

Even without a federal mandate, however, E-Verify usage has increased. In 2011, barely a quarter of a million employers nationwide checked potential hires via E-Verify, but the most recent figure for 2025 shows the number of employers that have entered into what is termed an E-Verify Memorandum of Understanding has topped 1.4 million.

As might be expected given the patchwork legal requirements, the figures vary wildly from state to state. E-Verify use is widespread in states that have made it mandatory, such as Florida, with 2.4 million checks in 2025, or South Carolina, where there have been more than half a million. Even in California, there have been more than 2.6 million E-Verify checks this year, according to federal figures.

How It Works

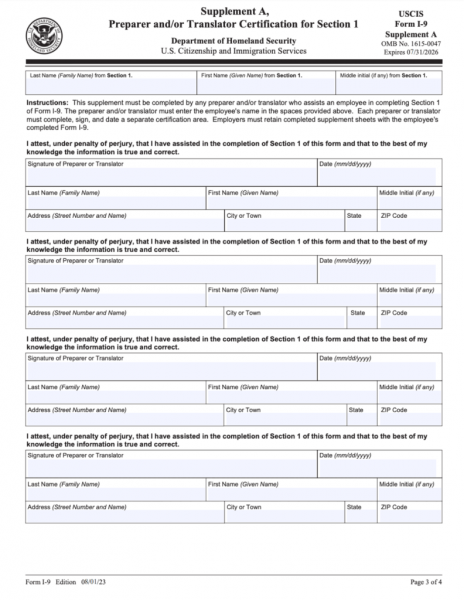

The E-Verify system is free for employers, although it does require some training, and businesses with many employees often outsource the job. When an employee begins work, they are expected to complete Form I-9, which includes their name, Social Security number, date of birth, and other relevant information. That is the same information entered into the E-Verify system, which then checks it against various federal records.

But the process involves only the employer and the computer; it doesn’t alert a U.S. citizen whose personal information has been checked in the system. It simply ensures that the pieces of information match those on record for the name of the person entered into the system.

The exact number of Americans whose Social Security numbers might be available to fool E-Verify isn’t clear, but authorities agree it’s large. The information is relatively easy to purchase on the dark web, and there have been some huge data breaches. In 2013, a breach at Yahoo may have touched 3 billion people, and last year, a class action lawsuit was filed against a now-defunct company, National Public Data, alleging identity information on some 2.9 billion people had been breached.

In FY 2024, the Social Security Administration’s inspector general received 78,588 allegations of misuse of numbers, while between April 1 and Sept. 30, 2025, it got another 26,822.

Another indicator of fraud is the rapid growth in the Social Security Administration’s “Earnings Suspense File,” which reflects the amount of taxes paid to the fund that can’t be matched with a U.S. citizen. The fund – which for many years was dominated by women whose maiden names did not match their married names – has skyrocketed in recent years largely because of illegal immigration. Between 1937 and the end of FY2021, the amassed money stood at $1.9 trillion. By the end of FY2023, the latest year for which numbers are available, that total had jumped more than 20%, to $2.3 trillion.

Even as identity theft has grown over the years, cracking down on it has become harder as a unanimous Supreme Court has whittled down the ways in which the Justice Department can charge people with aggravated identity theft. In 2009, the court ruled the person using stolen ID information had to have knowledge that the information had been stolen, and a 2023 decision said “aggravated identity theft is violated only when the misuse of another person’s means of identification is at the crux of what makes the underlying offense criminal.”

Nevertheless, the dockets of U.S. Attorney’s offices show multiple cases of aggravated identity theft in Florida, Arizona, and elsewhere. RCI asked the Justice Department and several U.S. Attorneys’ offices about the frequency of such cases and how they are trending in terms of time and geography. The Justice Department did not respond, while the different offices declined to comment.

Employers not using E-Verify can be easily fooled, according to several experts, as fake documents have become increasingly sophisticated and artificial intelligence is helping criminals, too.

“It’s no longer a cottage industry, it’s a mansion industry,” said Bob Griggs, the chief executive and founder of Verify I-9, a company that handles I-9 audits and E-Verify entries for employers.

Eva Velasquez, a former law enforcement officer who is now chief executive of the non-profit Identity Theft Resource Center, says personal information can be captured from lost wallets, stolen mail, online fraud, calls from conmen, and more. Children’s identity is especially attractive to thieves, and because they do not file quarterly reports, the scope of it all remains uncertain.

“There are IDs now where it’s almost impossible to detect they’re bogus just by looking,” she told RCI. “The overall figures ebb and flow, but the level of sophistication and variety of ways they are finding to steal identities is increasing exponentially, and the way we use data is increasing exponentially.”

Why It Isn’t Used

There are ideological reasons behind some states’ refusal to mandate E-Verify, such as left-wing lawmakers in California and Illinois, but opponents also advance economic arguments against it. Employers who prefer a low-wage labor market have never been enthusiastic backers of the system: the U.S. Chamber of Commerce opposed it until 2021, when the Supreme Court upheld mandated use in Arizona. The Chamber declined to comment on the issue to RCI.

One argument is that E-Verify raises many false flags, and it does so disproportionately against immigrants. Pro-immigration groups, including the National Immigration Law Center and the American Civil Liberties Union, cite errors as grounds for opposing the system, although the study most often cited found E-Verify returns a “Tentative Non-Confirmation” in just one of 400 cases.

That small fraction is hardly an indictment of E-Verify, according to Mortensen and others who compared it to issues women might have if they choose to change their last name after marriage.

California also contends that an E-Verify mandate would have an adverse impact on the state’s unemployment rate and drive already skittish immigrants further underground. Thus, E-Verify could actually hurt the state’s economy, especially in agriculture and other sectors that often rely on a transient workforce.

But those negative developments have not occurred in states that do mandate E-Verify. For example, South Carolina mandated E-Verify in 2012 when its GDP was $21.4 billion, and its unemployment rate stood at 9.9%. By 2024, South Carolina had a GDP of $34.3 billion, and its unemployment rate in August was just 4.3%.

The same is true in Georgia, where E-Verify has been required for companies with 10 or more employees since 2013. Since it made the move, Georgia’s GDP has doubled, and its August 2025 unemployment rate was 3.4%, according to Federal Reserve Bank figures.

Florida, perhaps surprisingly given its long-time Republican majority in Tallahassee and the governor’s mansion, did not mandate E-Verify until 2023, when it became required for all businesses with 25 or more employees. The move came one year after an illegal immigrant using a fake identity to get a construction job wound up killing an off-duty Pinellas County sheriff’s deputy in a heavy machinery accident. The Honduran national in that incident, 35-year-old Juan Ariel Molina-Salles, was sentenced last week.

That incident infuriated the community. “This company is employing a bunch of illegals, and they are all out there lying and giving us fake names, fake IDs, a lot of fake IDs out of North Carolina that really frustrated this investigation,” Sheriff Bob Gualtieri said at the time.

RCI reached out repeatedly to officials at economic departments in South Carolina, Florida, Georgia, and Arizona, asking about their experience with E-Verify, but none responded to questions.

Improving the System

Aside from an elusive federal mandate, perhaps the biggest improvement that could be made to E-Verify would be connecting it with state motor vehicle records. That way, a photo of the person's driver's license would provide a visual ID the system currently lacks. In some states, however, illegal immigrants can obtain valid driver’s licenses – there have been high-profile fatalities this year caused by immigrants given valid driver’s licenses – although the duplication would still raise a flag.

Another step to buttress E-Verify would be the more aggressive use of “no match letters,” according to Kirkorian. If the Social Security number does not match up on a tax return, the IRS is supposed to notify employers, and those letters, accompanied by ICE raids like the one in Nebraska earlier this year, would likely induce more widespread use of E-Verify.

“If you take these steps, and an employer does not fire unresolved identities, then there is proof someone is knowingly employing illegals,” Kirkorian said.

Installing additional layers of identification is also necessary to combat counterfeiters’ growing skill, according to Griggs.

“All of this is more related to industry than geography,” he said. “Somebody has found a counterfeiter and they’ve told their buddies and then you see it in clumps. We recently had a case where there were more than a dozen driver’s licenses in which the people had on the exact same black suit, the same white shirt and the same tie.”