Investigative Classics is a weekly feature on noteworthy past examples of the reporting craft.

People claim they don’t believe everything they read, but the rise of “fake news” suggests otherwise.

To appreciate how close we are to the dictum credited to P.T. Barnum – “There’s a sucker born every minute" – recall one of the finest bits of fantastic phoniness to ever grace the pages of a major publication: “The Curious Case of Sidd Finch” by George Plimpton.

Given that Plimpton was a famous literary prankster and that Sports Illustrated ran the article on April Fool’s Day 1985, readers might have discerned bunkum coming at them high and hard in the story of a 28-year-old “eccentric mystic” who could throw perfect strikes at 168 miles per hour, even though he'd never played organized ball. Throw in the similarly implausible claim that this prodigy was considering signing with the New York Mets – the Mets! – and the improbability dial cranked up past 11.

Nevertheless, as the New York Times reported years later:

When Sports Illustrated hit the newsstands several days before the April 1 cover date, "The Curious Case of Sidd Finch" staggered baseball and beyond. Two major league general managers called the new commissioner, Peter Ueberroth, to ask how Finch's opponents could even stand at the plate safely against a fastball like that. The sports editor of one New York newspaper berated the Mets' public relations man, Jay Horwitz, for giving Sports Illustrated the scoop. The St. Petersburg Times sent a reporter to find Finch, and a radio talk-show host proclaimed he had actually spotted the phenom -- who, truth be told, was back in Oak Park teaching art at Hawthorne Junior High.

Still, much credit is due. Plimpton worked his literary legerdemain by playing it straight, aping the in-depth sports feature-story format. These include quotes from Met coaches, owners and players as well as an assortment of honest to goodness facts:

The fastest projectile ever measured by the JUGS (which is named after the oldtimer's descriptive—the "jug-handled" curveball) was a Roscoe Tanner serve that registered 153 mph. The highest number that the JUGS had ever turned for a baseball was 103 mph, which it did, curiously, twice on one day, July 11, at the 1978 All-Star game when both Goose Gossage and Nolan Ryan threw the ball at that speed. On March 17, the gun was handled by [Met pitching coach Mel] Stottlemyre. He heard the pop of the ball in Reynolds's mitt and the little squeak of pain from the catcher. Then the astonishing figure 168 appeared on the glass plate.

Plimpton strains but doesn’t quite break credulity as he tells us that Finch was an orphan later adopted by “the eminent archaeologist Francis Whyte-Finch, who was killed in an airplane crash while on an expedition in the Dhaulagiri mountain area of Nepal.”

Not much else was known about his youth, except for a brief spell at Harvard. Plimpton heads off debunkers by stating: “The registrar's office at Harvard will release no information about Finch except that in the spring of 1976 he withdrew from the college in midterm … Finch's picture is not in the freshman yearbook. Nor, of course, did he play baseball at Harvard.”

He does include quotes from a roommate – who is pictured:

His assigned roommate was Henry W. Peterson, class of 1979, now a stockbroker in New York with Dean Witter, who saw very little of Finch. "He was almost never there," Peterson told SI. "I'd wake up morning after morning and look across at his bed, which had a woven native carpet of some sort on it—I have an idea he told me it was made of yak fur—and never had the sense it had been slept in. Maybe he slept on the floor. Actually, my assumption was that he had a girl in Somerville or something, and stayed out there. He had almost no belongings. A knapsack. A bowl he kept in the corner on the floor. A couple of wool shirts, always very clean, and maybe a pair or so of blue jeans. One pair of hiking boots. I always had the feeling that he was very bright. He had a French horn in an old case. I don't know much about French-horn music but he played beautifully. "

Finch reappeared nearly a decade later in Old Orchard Beach, Maine, where the Met’s AAA affiliate was playing. There he informed manager Bob Schaefer, “I have learned the art of the pitch.”

Schaefer wants to get back to the hotel but agrees – and here Plimpton expertly weaves in some pure Americana - to see if Finch can hit a soda bottle on top of a fence post.

He rears way back, comes around and pops the ball at it. Out there on that fence post the soda bottle explodes. It disintegrates like a rifle bullet hit it—just little specks of vaporized glass in a puff.

They talked and Schaefer remembers Finch telling him:

"He's never played before, but he knows the rules, even the infield-fly rule, he tells me with a smile, and he knows he can throw a ball with complete accuracy and enormous velocity. He won't tell me how he's done this except that he 'learned it in the mountains, in a place called Po, in Tibet.' That is where he said he had learned to pitch ... up in the mountains, flinging rocks and meditating. He told me his name was Hayden Finch, but he wanted to be called Sidd Finch. I said that most of the Sids we had in baseball came from Brooklyn. Or the Bronx. He said his Sidd came from 'Siddhartha,' which means 'Aim Attained' or 'The Perfect Pitch.' That's what he had learned, how to throw the perfect pitch. O.K. by me, I told him, and that's what I put on the scouting report, 'Sidd Finch.' And I mailed it in to the front office."

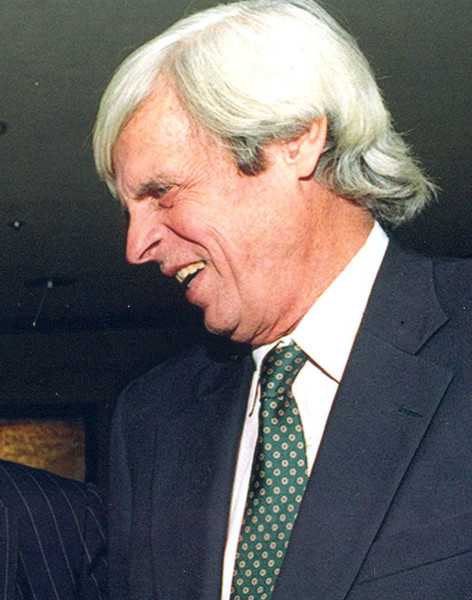

Although Finch has off-the-charts talent, there are two obstacles. First is his Buddhism, as explained by Dr. Timothy Burns (also pictured), the author of, among other treatises, “Satori, or Four Years in a Tibetan Lamasery.”

Reached by SI at the University of Maryland, where he was lecturing last week, Burns was less sanguine. "The biggest problem Finch has with baseball," he said over the phone, "is that nirvana, which is the state all Buddhists wish to reach, means literally 'the blowing out'—specifically the purifying of oneself of greed, hatred and delusion. Baseball," Burns went on, "is symbolized to a remarkable degree by those very three aspects: greed (huge money contracts, stealing second base, robbing a guy of a base hit, charging for a seat behind an iron pillar, etc.), hatred (players despising management, pitchers hating hitters, the Cubs detesting the Mets, etc.) and delusion (the slider, the pitchout, the hidden-ball trick and so forth). So you can see why it is not easy for Finch to give himself up to a way of life so opposite to what he has been led to cherish."

The second problem is Finch’s love for the French horn. Bob Johnson, artistic director of the New York Philomusica ensemble tells Plimpton:

I have heard many great horn players in my career—Bruno Jaenicke, who played for Toscanini; Dennis Brain, the great British virtuoso; Anton Horner of the Philadelphia Orchestra—and I would say Finch was on a par with them. He was playing Benjamin Britten's Serenade, for tenor horn and strings—a haunting, tender piece that provides great space for the player—when suddenly he produced a big, evocative bwong sound that seemed to shiver the leaves of the trees. Then he shifted to the rondo theme from the trio for violin, piano and horn by Brahms—just sensational. It may have had something to do with the Florida evening and a mild wind coming in over Big Bayou and tree frogs, but it was remarkable.

Not just remarkable, but almost unbelievable.