When a cyber worm dubbed “NotPetya” infected the systems of some 7,000 companies worldwide last year, few if any of them were prepared for the equivalent of a pandemic computer virus. It was a costly incident that caught many companies flatfooted.

Nuance Communications, which provides speech and imaging software and operates in 35 countries, lost $68 million in revenue last fiscal year due to the attack, according to company spokesman David Seuss. The company also had to pay $24 million in other expenses for “remediation and restoration.”

Such costs are becoming increasingly commonplace. According a McKinsey study published in March, companies spend nearly half a trillion dollars on cybersecurity defenses annually and suffer some $400 billion in losses related to attacks.

In response, many businesses are turning to an age-old protection against risk: insurance. But that has given rise to related concerns: Do the underwriters even know what they are insuring against? And in a worst-case scenario, could they be setting up the world financial system for a fall?

Some of the biggest names in the insurance industry, including AIG, CNA and Chubb, are now offering cyber policies to meet skyrocketing demand, as hackers wage attacks on computer systems seemingly at will around the world. There are no firm numbers regarding the size of the cyber insurance market, but most analysts say it has been growing at an annual rate of 20 to 30 percent since 2013. The data resource Statista estimates that about $4 billion in policies were sold in 2017 and expects that figure to rise to nearly double by 2020. Nearly every major company is mobilized to defend against cyberattacks.

But some industry experts warn that ever-evolving cyberattacks are far less predictable than, say, lifespans projected from actuarial data used to price life insurance policies. Many doubt that the business world is adequately insured against cyberthreats and, even if it were, whether insurers would be prepared to cover catastrophic losses.

Would cyber crooks be able to steal billions from major financial institutions? If so, would that cause a 2008-style global panic if the vulnerability were perceived as being worldwide?

“Cyber is the ultimate asymmetrical attack,” observes Jerry Caponera of Nehemiah Security, a cybersecurity firm, who notes the difficulty of “modeling” hackers and defenders against them as one would other, better-known risks. “Most companies overestimate their defenses, and underestimate their defenses.”

Insurers face similar problems in trying to price policies. The damage that can be inflicted by cyberattacks is wide-ranging and often hard to pin down. This can include specific dollar amounts stolen or extorted through ransomware, the loss of customer data (and the money required to notify and protect victims), the value of lost business and business opportunities, and damage to a company’s reputation.

A wide array of known cyber unknowns raises a range of knotty questions. For businesses, the vast majority of which will not be attacked, it is hard to determine whether it makes financial sense to purchase insurance at all.

The data breach of Target in 2013, for example, in which the personal information of as many as 70 million customers was stolen, put hard-to-quantify issues of trust into play. Because of these complications, insurers often try to tailor individual policies to the projected needs of customers.

The number of companies writing such policies continues to increase – to 170 companies in 2017, up from 119 in 2016, according to Aon, a global reinsurance and risk intermediary. The study also found that the market remains profitable, as “industry loss ratios” (the difference between premiums charged and claims paid) “decreased in 2017 – from 47.6 percent to 32.4 percent, mostly due to a reduction in severity.”

A larger problem, however, may loom for the public because a catastrophic, system-wide attack could outstrip the ability of insurers to pay.

Christine Lagarde, managing director of the International Monetary Fund, suggested this in a June 22 blog post, warning, "An IMF staff modeling exercise estimates that average annual losses to financial institutions from cyber-attacks could reach a few hundred billion dollars a year, eroding bank profits and potentially threatening financial stability.”

Informing such worries is the 2008-2009 meltdown, which was triggered by credit default swaps, obscure derivatives held by most global financial institutions that were not insured by conventional deposit insurance – thought to hold some $60 trillion in notional value at the end of 2007. Even AIG, one of the world’s largest insurers currently selling cyber insurance, was bailed out during the last crash because of its exposure to swaps. Now the hyper-networked nature of the information economy introduces new vulnerabilities. If anything, the opportunities for attacks have greatly multiplied since 2008.

“AIG saw as many [cyber] claims notifications in 2017 as in the previous four years combined, receiving the equivalent of one claim per working day,” the company stated in a recent report, noting that “many of these losses were uninsured” because, for example, companies had the wrong kind of coverage.

In many instances, such as the epic security breaches at Equifax, Target and Yahoo, there are billions of dollars at stake. Although major companies will not address this subject on the record, they may be coming up short on cybersecurity measures and the insurance they buy to cover potential losses.

Eighty percent of cybersecurity professionals surveyed by ISACA, a technical trade association, said it was either likely or very likely their enterprises would experience a cyberattack this year.

“The threat landscape is rapidly becoming much more problematic than has been the case historically,” is one conclusion in ISACA’s State of Cybersecurity 2018 report. “Not only are enterprises witnessing an increase in the number of attacks, but these attacks continue to evolve.”

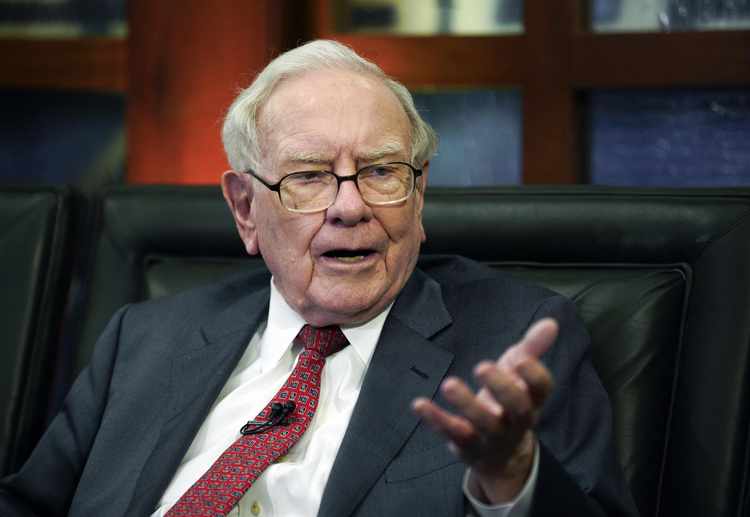

Warren Buffett, for one, is highly skeptical of whether there’s enough cyber insurance protection. Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway owns several insurers, although he says he’s reluctant to gain more exposure to cyber risks.

"Cyber is uncharted territory. It's going to get worse, not better," Buffett said at Berkshire’s annual shareholders meeting on May 5. "There's a very material risk which didn't exist 10 or 15 years ago and will be much more intense as the years go along."

Cyberattacks are hard to defend against because they are increasing in frequency and variation and require extensive time and resources to fix.

The McKinsey study found:

- Companies need about 100 days on average to detect a covert attack.

- About 100 days before discovery of attacks a hundred billion lines of code are created.

- There are 120 million new malware variants every year and thousands of attacks on each company every month.

- The growing “Internet of Things” trend that links machines like home appliances and security systems to online networks will add 50 billion new devices to the Internet.

Most industries refuse to detail their preparations for future attacks. As companies seek to protect against risk by purchasing insurance, they may buy less coverage than they need, and mistakenly assume that they will be paid even in the event of a systemwide attack. But many if not most companies surveyed may not have enough coverage for a catastrophic attack, notes a blog by Aon.

So far, such a crippling blow has not been delivered. But damage has been considerable. The NotPetya virus that compromised Nuance Communications also gobsmacked the pharmaceutical giant Merck, reportedly costing the company more than $300 million while hobbling its email, sales, research and manufacturing operations for more than a month.

Similarly, another NotPetya victim, the Danish shipping goliath Maersk, estimated that it lost some $300 million in business and took two weeks to get fully operational. The malware shut down systems at the Port of Los Angeles, one of the busiest container terminals in the world. The company would not comment on the attack.

All told, the NotPetya cyber attacks cost businesses some $10 billion in revenue – and that was just one virus assault.

Due to the asymmetric and unpredictable nature of cyberattacks, the next financial meltdown will not be as easy to anticipate -- nor fix. As the McKinsey study noted, “the threat is growing – as much in intensity as in numbers.”