Update, May 29, 2018: Eric Greitens, the embattled Republican Missouri governor facing a sexual misconduct scandal and allegations of misuse of a charity donor list, has announced he will resign this week. - Fox News

Eric Greitens was a novice political outsider when he won the Missouri governor’s race in November 2016, vowing to show the Show Me State a drained swamp. But even in his first year in office, Republican strategists and insiders were sizing up the former Navy SEAL as a future presidential contender. Eighteen months earlier, Greitens hadn’t even been a Republican. And today, 18 months later, it’s unclear whether he’ll even finish his first term in office.

In February a grand jury in St. Louis indicted Greitens on a felony charge of invasion of privacy. The charge stemmed from a compromising nude photo he allegedly took and “transmitted” of a woman with whom he had an affair in 2015. The governor’s trial was to begin May 14, but the prosecutor abruptly dropped the charge on that day and the case was dismissed.

Despite this turn of events, Greitens still faces possible impeachment later this year — by a state legislature overwhelmingly controlled by his own party. Accusations against Greitens – including “stealing” a donor list from a charity he founded — may or may not prove to be true. But what is already undeniable is that the governor has made enough enemies in his short time in office that the very establishment he pledged to confront has come for him with a vengeance.

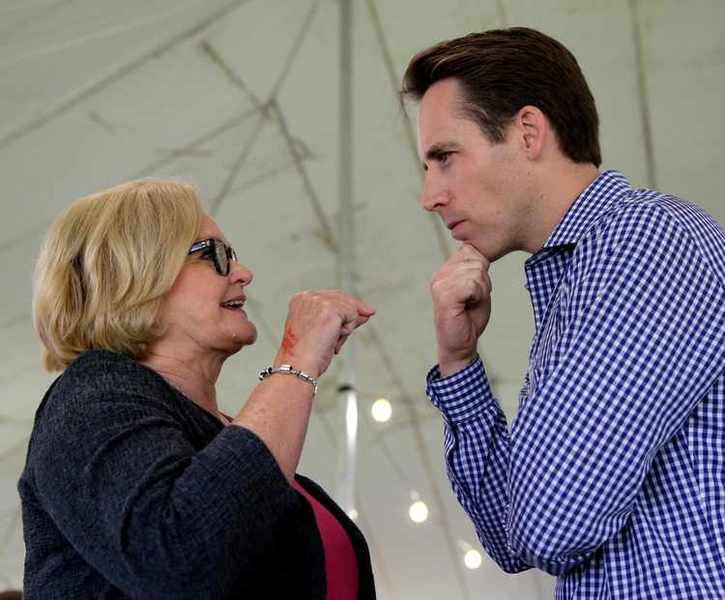

Attorney General Josh Hawley, for example, who wants to be the GOP nominee to contest Democrat Claire McCaskill’s Senate seat, has now called on Greitens to resign, after allying with the governor on key reforms last year.

At this populist moment, when President Trump and his supporters complain about a rigged system that mostly serves the interests of those in power, the governor’s backers believe that whatever his personal flaws, Greitens is an illustration of how the status quo can punish reform-minded outsiders. He made the rookie mistake, they say, of attacking a sacred cow of both Democrats and Republicans.

Greitens won the governor’s race by six percentage points — the same night that Trump carried Missouri by nearly 20. A Missouri native, Greitens was new to politics — and to the GOP. He publicly broke with the Democratic Party only in July 2015. Three months later, he announced his campaign for governor.

On election night, then, one might have forgiven Republicans inclined to question his conservatism. But since taking office he has dispelled such doubts. He signed legislation making Missouri a right-to-work state, limiting unions’ ability to compel membership; ushered through tort reform to reduce large court damage awards; and pushed for choice in public education. And in December Greitens — perhaps fatefully — succeeded in shutting down, for this year at least, Missouri’s Low-Income Housing Tax Credit system. The governor’s allies firmly believe this was his real crime in the eyes of his adversaries.

This and other tax credits have long been a red line for Missouri legislators, one that has allowed them to subvert the will of another group of outsiders – the voters.

Back in 1980, at the start of the Reagan revolution, voters approved a constitutional amendment limiting state government spending to 5.6395 percent of the personal income of Missourians. But there was a loophole: Tax credits outside the appropriations process are excluded from the definition of total state revenue. So lawmakers discovered that the way to exceed the cap was to structure additional spending as tax credits to compensate developers, contractors and investors, not as checks doled out directly.

Missouri had 63 such tax credit programs as of 2017, but the seven biggest account for more than three-quarters of the credits redeemed in recent years. In fiscal year 2016, the low-income housing credit alone accounted for 30 percent of credits redeemed. It also represents about 72 percent of outstanding credits—nearly $828 million worth. These are credits that have been issued but not yet redeemed, and whose redemption is to some extent at the discretion of the holder of the credit. Another $476 million in credits have been “obligated” to projects, but not yet issued.

The low-income housing credit is easily the largest tax-credit program in Missouri, with its own powerful constituency. On a per capita basis it’s the largest state low-income housing program in the country. And it’s hugely inefficient. In 2017 the state auditor estimated that every dollar spent on the low-income housing credit produced just 12 cents of benefit to the state. What’s more, just “$[0].42 of every credit dollar actually [goes] toward low income housing projects.” The rest, according the auditor’s latest report, goes to investors, tax-credit syndicators and taxes owed the federal government. With credit redemptions averaging $150 million a year in recent years, that’s $87 million diverted annually.

Previous audits have returned similar conclusions and recommended reforms. Greitens’ two most recent predecessors both called on the state legislature to fix the program, to no avail.

Greitens went further. He used his effective control of the 10-member board that oversees the tax credit – the Missouri Housing Development Commission – to zero them out.

One of those commissioners was Jason Crowell, a former state representative, former Republican majority leader in the lower house and former state senator. Crowell relinquished his seat in January. If he had stayed, he says, “the tax credit community would have killed my nomination,” in part for his vote to kill the program for this year.

As a senator, Crowell was a vocal critic of the credit and actively campaigned for reform of the system. He says he has no problem spending money on housing programs for the poor. “But if we spend a dollar on low-income housing, we want a dollar to go to low-income housing,” as he puts it.

Developers and syndicators that profit from the tax-credit program stand to gain if Greitens is impeached. He would be succeeded by Lt. Gov. Mike Parson, who voted against stopping the tax credits last fall and has long defended the program. Political action committees associated with Steve Tilley, a former speaker of the state house who is now a lobbyist representing beneficiaries of the program, contributed more than $10,000 to Parson’s campaign vehicle, all of it coming after Greitens started to move publicly against the program.

One Republican state representative, who asked not to be named out of fear of retaliation, described Parson as “tight with the housing guys” and Tilley. This representative supports Greitens’ goal of reforming or replacing the housing credit, but also believes he is guilty of “taking the picture” and of improprieties related to The Mission Continues, a charity Greitens founded before running for office. He is in favor of removing Greitens from office, and the sooner the better: “I’d rather have a governor I disagree with who isn’t a crook, than a crook I agree with,” he said. As for Parson, the lawmaker said “he sells out to lobbyists the old-fashioned way,” taking campaign contributions in return for policy support without crossing legal lines, in his view.

The governor’s supporters say that it is not just his actions, but his rhetoric, that has aroused the enmity of his party. In 2016 he ran hard on draining the swamp and driving off what he saw as the crooks running Jefferson City. After he won, he didn’t let up on the language, even with his party in control of seven out of 10 seats in both houses of the legislature.

State capitals are all, to some extent, old boys’ clubs. Former reps and senators hang about, converting their knowledge of the system into lobbying, or political consulting, or sinecures on state commissions and departments.

Greitens stood outside all of that and has been determined to stay that way. He didn’t open the governor’s mansion to legislators for regular social events during the legislative session, as his predecessors have done. Instead, he went to war.

One longtime Republican strategist said, “He gave a stiff-arm to the legislature from day one. He basically told the legislature [to] do what I want you to do and go f--- yourselves.” Now a couple hundred people in the state house who have had to listen to their governor call them crooks for two years have an opportunity to return the favor. And even many who support his agenda seem to have little sympathy for his predicament. The state representative who called him a crook freely admits that the forces driving and funding the campaign against Greitens “aren’t good people.”

Greitens' opponents include Scott Faughn, the owner and publisher of the Missouri Times, an insider’s paper for the state government crowd, who delivered $50,000 in cash to the lawyer representing the ex-husband of the woman with whom Greitens had the affair in 2015.

Faughn has variously said he paid the money out of his own pocket to “buy” the ex-husband’s tape of the woman’s account of the affair (even though the lawyer provided the recordings freely to other media) and that he was paying to retain the lawyer, Al Watkins. Faughn wrote in the Missouri Times on May 3 that “[t]he money I used to buy the tapes was my money. There is no huge conspiracy, that is another lie and distraction tactic.”

Watkins has said that Faughn told him the money came from a “wealthy Republican guy” who wanted to ensure that the ex-husband had a “soft landing.” Watkins took a photograph of the neatly stacked and wrapped $100 bills and reported the money to the FBI because he couldn’t be sure of its source. Watkins has not responded to a question about whether Faughn is his client.

The House Investigative Committee has said it will subpoena Faughn to testify. Jay Barnes, the committee chairman, did not respond to a question about whether that subpoena has been issued.

Under Missouri law, Barnes’ committee has 30 days from the end of the legislative session on May 18 to complete its work. It’s clear that many in the legislature would like that work to end with a bill of particulars leading to impeachment. Crowell, for his part, doesn’t see the need to rush. With the felony case in St. Louis dismissed but not dead – the prosecutor said she could reopen it – Crowell argues that the legislature can afford to let things run a bit, gather all the facts (including those regarding the bags of cash and the interest groups supplying them) and come to a considered judgment on whether to overturn the will of the voters.