Bruce Wilkerson entrusted most of his life savings to a broker-adviser, telling him to “conservatively invest” his earnings from a decade in the National Football League.

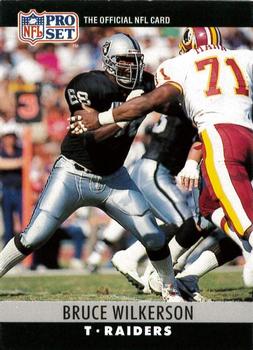

As a 6-foot-5, nearly 300-pound offensive lineman for the Los Angeles Raiders, Jacksonville Jaguars and Green Bay Packers, Wilkerson’s career was marked by success, culminating in a Super Bowl XXXI ring with Green Bay, where he protected the “blind side” of Hall of Fame quarterback Brett Favre.

But Wilkerson’s retirement has been thrown for a painful loss. The financial manager who was supposed to be protecting Wilkerson was stealing from him instead. Robert A. Gist of the Resource Horizons Group LLC stole $5.4 million from 33 investors, including $610,000 from Wilkerson.

The securities industry self-regulator, the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, or FINRA, took action. Along with the Securities and Exchange Commission, it imposed a $4 million arbitration award against Resource Horizons. Gist separately agreed to pay to pay $5.4 million to settle SEC charges that he had used customer funds for personal use.

In March 2015, arbitrators handed Wilkerson an apparent win: An award for all the money he lost. But neither Gist nor Horizons paid up. The firm dropped its registration with FINRA and filed for bankruptcy.

“I had been with this guy since my rookie year,” Wilkerson said of Gist. “I thought I invested well while playing, then I got this email and the firm went bankrupt and closed its doors. I blame myself.”

Wilkerson said he “has not been able to collect one cent of the award. I thought I was going to be retiring comfortably in a few years and now I will have to work for many more. The money would’ve made my life easier, since my body is beat up.”

In 2016, Gist pleaded guilty in federal court to defrauding investors of nearly $7 million total and is now serving time in prison.

Unpaid awards to wronged investors have been a problem for decades. Most brokerage customers enter into relationships with one hand tied behind their backs: When they sign up with brokers regulated by FINRA, they also sign away their right to sue.

If investors have a dispute with brokers – or have been fleeced – they are usually urged to go through FINRA’s arbitration forum, which sidesteps the court system. For many, it’s the only way to recoup their losses, although it often requires legal representation and is often criticized as being hostile to investors. Most wronged investors choose not to go through arbitration.

Even when investors win in arbitration, they often lose not only their life savings but a chance to get their money back. Firms often go out of business, evade regulators or simply refuse to pay. Nearly 30 percent of total damages awarded to investors went unpaid from 2012 to 2016, according to the Public Investors Arbitration Bar Association, a trade group of lawyers who represent investors. In 2017, 28 cents out of each dollar awarded went unpaid. All told, investors have been stiffed some $220 million during that period.

Deadbeat firms often flout regulation and fines or simply file for bankruptcy. Marnie Lambert, a former president of the lawyers’ group and an attorney in Columbus, Ohio, observes: “The firms are not paying because they’re going out of business and going out of business because they don’t want to pay.”

FINRA was formed in 2007 through a merger of the National Association of Securities Dealers and the New York Stock Exchange's regulatory operations. Policing more than 630,000 broker-advisers, it describes itself as "the largest non-governmental regulatory organization for securities brokers and dealers doing business in the United States."

But as far back as 2000, the Government Accountability Office faulted its predecessor, the NASD, for falling short on protecting investors over the previous two decades. FINRA only started to partly disclose unpaid award data in 2011, with more complete reporting emerging in 2015.

Unlike the banking industry, the brokerage business has no comprehensive safety-net fund or agency such as the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation; the industry won’t pick up the tab for wronged investors when (typically smaller) brokerage firms don’t pay.

The one safety net that brokerage customers have – the Securities Investor Protection Corporation – protects only up to $500,000 in cash in a brokerage account if a firm fails. It doesn’t cover unpaid arbitration claims, however, most of them dodged by firms that simply aren’t funded well enough to pony up. And if firms get into trouble with FINRA, they are even less likely to pay.

“It is important to note that most unpaid customer arbitration awards are against firms whose FINRA registration has been terminated, suspended, canceled or revoked, or who have been expelled from FINRA,” the regulator noted in a recent statement.

Michelle Ong, a spokesperson for FINRA, said in a prepared statement that the organization “has taken many steps in recent years to use the tools within its power to help customers recover the awards they are owed. This issue is unfortunately not unique to FINRA’s forum or the broker-dealer industry.

“Fully addressing the issue of customer recovery requires an approach that takes into account the different channels through which customers receive financial services and prevents regulatory arbitrage between them.”

In a discussion paper in February, the regulator said it is seeking comment on “proposed amendments to its rules designed to create further incentives for the timely payment of awards by preventing an individual from switching firms, or a firm from using asset transfers or similar transactions, to avoid payment of arbitration awards.”

Since most brokerage customers are unable to sue and are not protected by stringent fiduciary legal standards that put investors’ interests above those of the firm, they are often lacking meaningful investor protection.

The Trump administration and courts have delayed the full implementation of the Department of Labor’s 2016 Fiduciary Rule, which would’ve curbed broker abuses by those who offer retirement advice and products.

The rule’s full rollout has been postponed until July 1, 2019, as various legal challenges wind their way through the court system. A recent ruling in the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals struck down the rule, which may be appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Elsewhere, the Dodd-Frank banking overhaul of 2010 gave the SEC a mandate to write and enforce a "best interest" or stricter fiduciary rule protecting investors from broker-adviser abuses.

Last week the SEC approved a draft of a new "best interest" rule for public comment. Since the rule doesn't require broker-advisors to become fiduciaries, it's unclear whether broker abuses will be significantly curbed. Less investor-friendly "suitability" standards will still apply -- unless the financial professional is a registered investment adviser, certified financial planner, chartered financial analyst or other fiduciary. The rule also would not create a pool of money to help investors whose brokers didn't pay arbitration awards.

The lawyers group for investors has proposed that FINRA create just such a fund. To that end, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) has introduced legislation with the group’s input to set aside money collected by FINRA from member fines to cover unpaid awards.

"Unpaid arbitration awards have cost ordinary investors hundreds of millions of dollars over the years,” Warren said in a statement. “FINRA is supposed to be looking out for them, not the brokers and dealers who cheat them."

Today, decades removed from “the best feeling in the world” – winning his Super Bowl ring – Wilkerson says he has only a little money in a 401(k). To make ends meet, the 53-year-old works as a machinist in an aluminum plant in eastern Tennessee. He says he’s speaking out to “stop this from happening to others.”