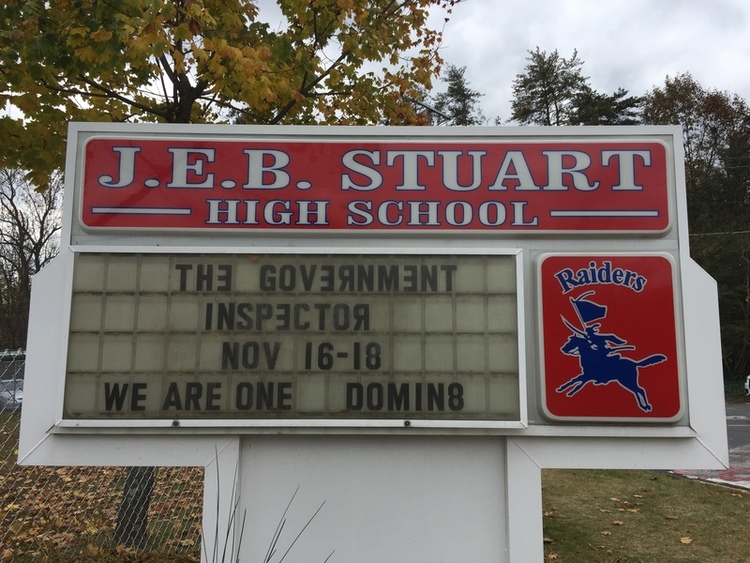

After more than two years of divisive debate, students in Falls Church, Va., can consign J.E.B. Stuart High School to the dustbin of Confederate history: The place has been renamed Justice High School.

“It should be a no-brainer by now that Confederate names should be gone,” said Nebal Maysaud, a 2013 graduate of the ethnically mixed school, who supported the name change ratified by the Fairfax County School Board in October.

The names of Confederate general Stuart and his compatriots are disappearing from school entrances and walls around the country. The Southern Poverty Law Center identified 109 schools with Confederate-inspired school names in April 2016. Since then at least 19 have embraced new, less historically freighted names, with many more considering changes.

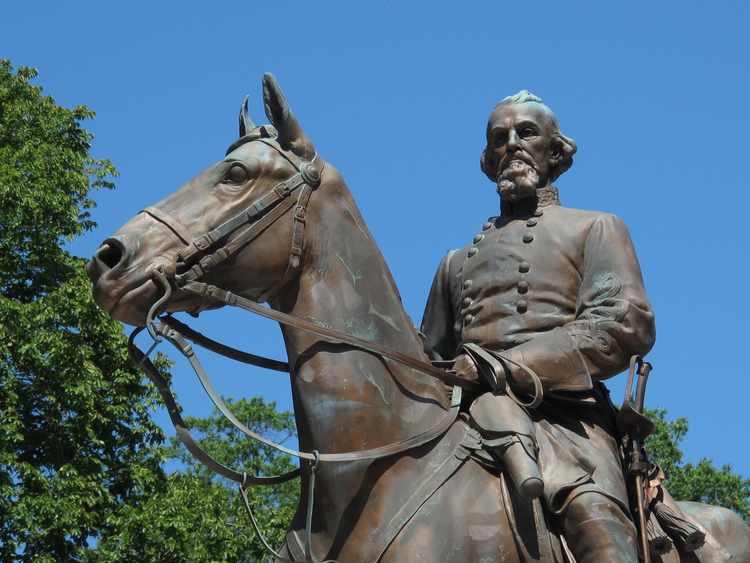

The renamings have been quietly gathering momentum alongside more visible and boisterous efforts to raze Confederate monuments – sometimes illegally and in the dead of night – since deadly violence broke out last summer over plans to remove a Robert E. Lee statue in Charlottesville, Va. Those protests resulted in the death of activist Heather Heyer, who was run down by a car driven by a neo-Nazi, and has since become a martyr to the movement.

The trend is also a continuation of what’s been happening on and off at the local level for years – notably after the 2015 massacre of nine black churchgoers in Charleston, which prompted the removal of the Confederate flag from the South Carolina statehouse.

And as in the past, renamings and other efforts to expunge Confederate commemorations once again raise questions about the wisdom of judging the past by modern standards, and about where such efforts might end in a country with so many potential targets -- a concern raised by President Trump after Charlottesville.

Never mind the Civil War: There are many schools and other places named for Americans now identified with the nation’s racist past who had little or nothing to do with the Confederacy. They range from President Woodrow Wilson to slave-holding Founding Fathers.

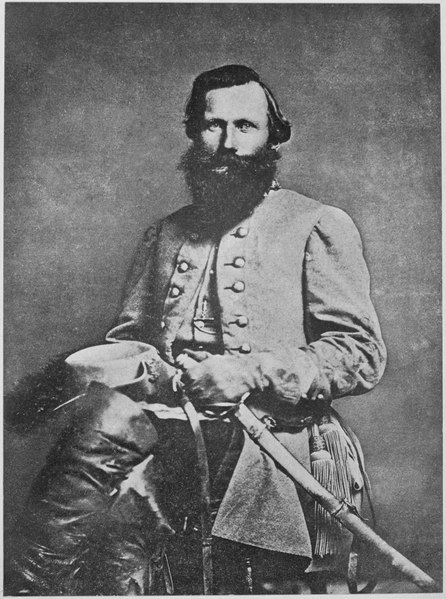

Of the 109 schools identified by the SPLC, Confederate commander Robert E. Lee led the pack, accounting for nearly half. Stonewall Jackson and Jefferson Davis came in a distant second and third place with 15 and 13 namesake schools, respectively. Following with seven schools were Nathan Bedford Forrest, a Confederate general who became an early leader of the Ku Klux Klan, and P.G.T. Beauregard, the Confederacy's first prominent general. While over a third of these schools were built or dedicated between 1950 and 1970 – in clear opposition to the civil rights movement -- many are even older.

However well-intentioned the renaming campaigns may be, many oppose them as just more reflexive – and expensive -- political correctness. Early estimates for the cost of the J.E.B. Stuart to Justice High School transition, for example, run as high as $800,000.

And such campaigns take place on an easily accessed playing field, where participation can require little more commitment than clicking “sign” on a Change.org petition.

Victor Davis Hanson, a conservative scholar at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, said the name-revision debates allow for “a sort of virtue-signaling at no personal cost,” abetted by the Internet. “Anonymity and instant electronic referenda encourage hysteria and groupthink,” said Hanson.

They can also give a relatively small group of committed activists outsized influence. Public opinion polls taken following the violence in Charlottesville show most Americans prefer to leave Confederate monuments in place. An August Reuters-Ipsos poll, for example, found that 54 percent of adults said Confederate monuments “should remain in all public spaces.”

A November poll of residents in 11 Southern states conducted by Winthrop University found only 5 percent of all respondents – including 20 percent of African-Americans -- supported the complete removal of Confederate statues.

Yet school name debates are expanding into the heart of Dixie. Huntsville, Ala., for one, is seeing a surge in name-change sentiment.

“The name of our school should stand for unification, rather than separation,” said a student at the local Lee High School, in a video collection of student pleas for a name change. The accompanying Change.org petition proposes renaming the school after Paulette Turner, who in 1964 became its first black student.

As recently as 2011, however, suggestions by then-Superintendent Casey Wardynski to rename the school while transitioning to a new building were shot down by students and community members.

In El Paso, Texas, concerns about the appropriateness of a road named for Robert E. Lee sparked similar conversations about the local Robert E. Lee Elementary School — but with a result different than elsewhere.

Was a change needed? “From the students, teachers, administration, to the community members, the answer was an emphatic no,” said school board member Diane Dye. “They like their school name and their school’s colors.”

Maysaud, the son of Lebanese immigrants, said that when he attended J.E.B. Stuart High, the student body tended to ignore the name’s connotations, even students like him who were discomfited by them. Today, however, is a different story.

“We knew racism was around, but had no avenue to talk about it,” said Maysaud. “Now the social climate has changed.”

Caroline Janney, a professor at Purdue University specializing in the Civil War and how it has been remembered, said the sight of white supremacists and neo-Nazis attaching themselves to Confederate monuments and symbols changed their meaning for many people.

While renaming a school might seem like a superficial fix if the aim is more minority student engagement -- one of the more successful counter-arguments made in these debates – the prevailing view seems to be it could make for a more positive educational experience.

At the very least, there was something incongruous about a heavily Hispanic school with a 76 percent minority population in 2017 bearing the name of a Confederate general, as was the case with J.E.B. Stuart High in Falls Church.

Echoing President Trump, those resisting the name changes at Stuart and elsewhere fear that purging historical figures from public spaces could be a slippery slope. Case in point: the recent decision by an Alexandria, Va., church to remove a plaque honoring George Washington in conjunction with removing a plaque honoring later church member Robert E. Lee.

Hanson notes that it would be easy to get caught up in the fervor of cleansing an unsavory past, and collapse significant distinctions between people that lived in an entirely different time and place from the world we now know.

Certainly, there is nothing wrong with deciding that it is time to pick a more inspirational namesake, although a 2007 Manhattan Institute study found that school districts were increasingly playing it even safer and eschewing person-inspired names for location-based ones. Duval County, Fla., did so in 2014 with Westside High School, previously named for Nathan Bedford Forrest.

Meanwhile, there are already 19 schools named for President Barack Obama and two for his wife, Michelle. The late Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall has 35 namesake schools, according to data from the National Center for Education Statistics. During the Falls Church debates, Stuart High was in serious contention to become the 36th.

Some schools have opted to save the money required by a school change – including costs for new signs, school uniforms, team logos, etc. – by making the old name mean something new.

A San Antonio, Texas, school district did just that last month, announcing that its Robert E. Lee High School would change to the Legacy of Educational Excellence School-- or L.E.E., for short.

In 2016, The New Orleans Advocate reported that Robert E. Lee High School in the East Baton Rouge Parish likewise considered turning Lee into an acronym. Ultimately, the school board voted just to drop the Robert E. from the name in a 5 to 4 vote. At the time, school board member Connie Bernard estimated that just changing the school’s sign would cost $250,000.

In Fairfax County, the school board is banking on those who supported the change from Stuart to Justice High to pony up the necessary funds.

“We’re hoping that the 40,000 people who signed the petition and said they cared about this would help us out,” said school board member Sandy Evans.

Maysaud said he’ll be glad to contribute, and hopes others will, too. Perhaps even some of the celebrity alumni that thrust Stuart into the national spotlight with -- what else? -- a Change.org petition.

“I’m still waiting for Julianne Moore to come through with a big check, as I think the rest of us are,” Maysaud said.