In September, after huge protests against the authoritarian regime of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro resulted in some 125 deaths, Donald Trump — not known generally for speaking out on international human rights — called for Venezuelan democracy to be restored, warning of further sanctions if it weren't.

China took a very different stand. In the wake of Trump's comments, its foreign minister, Wang Yi, took pains to reassure the Venezuelan government of Beijing's continuing support.

Wang presented this as part of China's policy of strict non-interference in the internal affairs of other countries. But some observers noted that Chinese policy on Venezuela is itself a kind of interference – on behalf of Maduro, whose crackdown on dissent has included essentially eliminating the country's once vigorous national assembly.

China, along with Russia, “has provided capital, goods, services, and political backing that has indirectly enabled the populist regime to ignore and ultimately destroy the mechanisms of democratic accountability,” Evan Ellis, an expert on Venezuela at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told a House hearing in September. What China and its Russian partner in this want, Ellis said, may in fact be “a transition away from the Maduro regime,” but “they are hoping they can get a transition to an equally anti-U.S. authoritarian regime.”

China is on the rise – that's clear and undisputed – and that rise is generally viewed in the traditional terms of great-power rivalry. The subjects most talked about, for example, during Trump's splashy visit to Beijing included the American-Chinese trade imbalance most of all, but also China's aggressive behavior in the South China Sea, its buildup of armed forces, and its threatening rhetoric toward American allies like Japan and Taiwan.

But perhaps the greater challenge presented by China's emergence lies in another role made possible by its newfound wealth and power – as the main model and enabler of a new authoritarianism sweeping much of the world.

From Russia to Venezuela, Thailand to Turkey, Hungary to the Philippines, Ethiopia to Cambodia, elected strongmen, military juntas, and one-party dictatorships are in power, in many ways reversing the trend toward liberal democracy that followed the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991.

China didn't bring about this authoritarian resurgence. Nor does it seek actively to spread its own authoritarian system around the world. But the means that China uses to consolidate its own regime, combined with its economic power and its formal disavowal of what it calls “Western values,” have made it almost automatically the leading country, and the center of gravity, in what some political scientists are calling the Authoritarian International.

President Trump, in his evident admiration for strongmen, can be said to be pragmatically accepting the new order. But this new reality, more than other U.S.-Chinese differences, is sharpening the two countries' longstanding rivalry into a global contest between the Western ideals of limited government and individual rights and competing notions of state power and control.

“China's rise has spread authoritarianism,” Ely Ratner, a former national security adviser to Vice President Joe Biden and now a fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, told RealClearInvestigations in a phone interview. “This is happening mainly because of China's domestic issues. China doesn't, for example, favor internet sovereignty because it wants Angola to have internet sovereignty, but because it wants to protect what goes in and out of its own borders.”

The result, however, is that internet sovereignty — think China's “great firewall” to block foreign websites -- has a certain standing as a legitimate exercise of government power, contradicting and defying the standards that Western democracies have tried to promote.

Moreover, departing from past caution, China has lately asserted that its authoritarian system -- expressed in the phrase “socialism with Chinese characteristics” -- is a viable and preferable alternative to Western liberal democracy.

“The Chinese path offers a new option for other countries,” President Xi Jinping said in a much-noted portion of the 3½-hour speech he made last month at the 19th Congress of China's Communist Party, held just days before Trump's arrival in Beijing. “It offers Chinese wisdom and approach to solving problems facing mankind.”

By the “Chinese path,” Xi seemed mostly to be talking about the country's extraordinary economic development -- but this was at a gathering that enshrined him as China's most powerfully autocratic leader since Mao.

Things weren't supposed to end up this way. For years, Western experts and policymakers predicted that China’s move toward free markets and global trade would spark political reform, a relaxation of a centuries-long impulse toward dictatorship. The need for free exchanges of ideas and information, the thousands of Chinese students studying in American universities, the emergence of a large middle class – all would push China toward a freer society.

But Xi's emergence demonstrates that the “Chinese path” means not just state-directed capitalism, but also one-party control, a gigantic, all-powerful security police, pervasive censorship, the imprisonment of dissidents, and a press and judiciary obedient to the dictates of the rulers.

A stern reaffirmation of this came three years ago when the Central Committee, clearly at Xi's behest, published what has come to be called Document No. 9, which essentially banned advocating seven “Western values,” including “civil society,” “Western constitutional democracy,” and “the West's idea of journalism.” Along those lines, China's media offer a near daily litany of the faults of Western parliamentary democracy -- its supposed wastefulness, the chaos it spawns, the inevitability of its decline -- while extolling the superiority of “socialism with Chinese characteristics.”

In some respects, China resembles the old, defunct Soviet Union, as both a great power and ideological rival of the West. But China is something the world hasn't seen since the end of World War II: a dictatorial, anti-democratic power that is, unlike the Soviet Union, an economic powerhouse. And it has used its diplomatic strength to weaken the efforts of the liberal democratic countries to promote human rights while defending and protecting authoritarian practices throughout the globe.

For example, China claims -- as it did in the Venezuelan case -- to observe the principle of strict non-interference in the affairs of other countries. But in practical effect that has meant opposing the major change to international behavior that took place after the Nuremberg trials of Nazi war criminals -- namely, to hold the worst violators of human rights to legal account, as the Western powers did by bringing Serbian leaders to trial in the wake of the Balkan wars of the 1990s. China's opposition began 10 years ago when it used its veto in the Security Council to defeat sanctions against Zimbabwean strongman Robert Mugabe.

Beyond this, it appears China is apt to befriend strongmen shunned or criticized by the West -- Cambodian autocrat Hun Sen, for example. For years, Hun Sen, wary of offending Western aid donors, exercised some restraint on his repressive impulses, experts on Cambodia noted -- even allowing opposition figures to run against him in elections. But that restraint has faded in recent years as China has invested billions in the country.

Last year, as journalist Sebastian Strangio has reported, Hun Sen defied a European Union demand that he cease his brutal crackdown on political opponents, praising China for its “no-strings support.”

This year, the repression in Cambodia picked up markedly when the country's main opposition figure, Kem Sokha, was arrested and charged with treason. Western countries protested the arrest. China did not.

Similarly, two years ago, after the International Criminal Court in the Hague charged Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir with war crimes in Darfur, China gave him a red-carpet welcome in Beijing. “You are an old friend of the Chinese people,” Xi told him.

In Thailand three years ago, after a military junta took power from the elected government, China was quick to establish cordial relations with the coup leader, Prayuth Chan-ocha, even as the United States, Thailand's most important ally, criticized him. Thailand then acquiesced to a Chinese demand that it send back to China nearly 100 members of China's persecuted Uighur minority who were seeking passage to Turkey — ignoring pleas not to do so from several Western countries.

Elsewhere, when Prime Minister Viktor Orban came under criticism for advancing a nativist, authoritarian agenda in Hungary, China welcomed him in Beijing, where he and Xi declared a “bilateral comprehensive strategic partnership.”

Much of this diplomatic activity is aimed at deflecting Western criticism both of China and other countries. In June this year, Greece, which has been helped during a long period of economic difficulty by major Chinese infrastructure investment, vetoed a European Union effort to formally criticize China for its human rights violations.

The Greek move was seen by many in Europe as shameful in and of itself, but, perhaps more ominously, it showed a new Chinese ability to indirectly undermine the European Union as a force for global human rights.

There are even signs that China is seen by other authoritarian countries a model both for economic growth and for the techniques it has developed to maintain tight political control. The New York Times recently reported that China has trained the officials that maintain the repressive system of surveillance and control in Ethiopia, Africa's second-most-populous country.

In recent years China has aggressively moved to establish multilateral organizations, such as the much-publicized Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank, that parallel and compete with similar organizations long dominated by the West. Again, the purpose of these institutions is generally to expand China's economic sphere, but, unlike their Western counterparts, they will not promote human rights, a free press, individual protections, and concepts like the independence of the judiciary.

Among these groups, for example, is the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, aimed at building ties among China, Central Asian countries such as Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, and Russia. Fighting terrorism is one of the ostensible purposes of the group, which created a Regional Anti-Terrorism Structure, or RATS, for the purpose. But human rights groups contend that the counter-terrorism effort is sometimes merely a disguise for suppressing domestic dissent. China has used it, successfully, to justify its demands that other member countries repatriate Uighur exiles, whom China brands as terrorists.

The Shanghai Cooperation Organization has also enshrined internet controls as a legitimate state activity. An agreement among the members signed in 2009, defined disseminating information “harmful to the spiritual, cultural, and moral spheres of other states” as a “security threat.” That would seem to be a justification for China's practice of banning websites from Facebook and Twitter to the online edition of The New York Times.

In a way, all of these aspects of China's behavior illustrate a conception of international affairs based on an unsentimental, cold-blooded assessment of its interests. China wants access to African raw materials; it is proposing its ambitious “One Belt, One Road” infrastructure project, making it the center of a new network of relations stretching from East Asia to West Europe. It doesn't pick and choose among the types of governments and leaders it deals with. It will deal with any of them so long as it sees some advantage in doing so. Many other countries are the same in this regard.

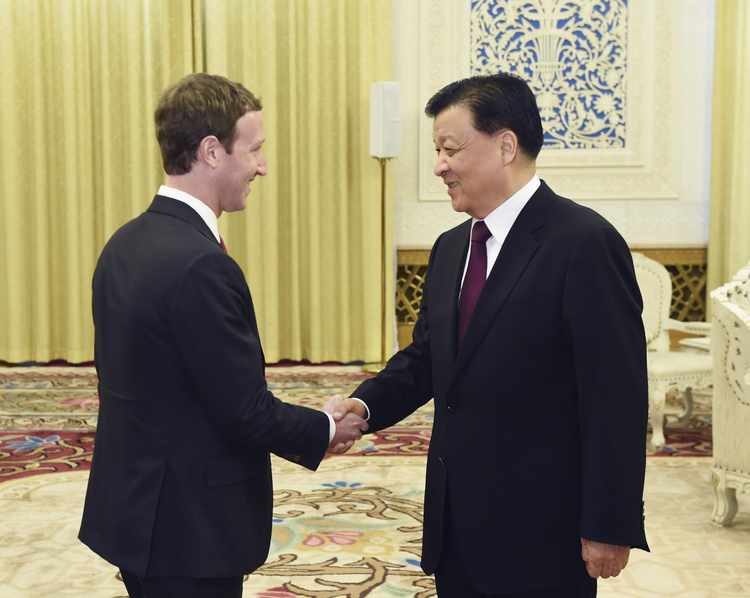

What is different about China is the way it has used its economic and diplomatic clout to compel others to not only to desist from human rights criticism of China but more generally to play according to China's rules. China has been remarkably successful in getting major Western entities, from Hollywood movie studios to Apple, to do so or risk being excluded from the benefits of a presence on the China scene. Following the party congress that enshrined Xi as China's most powerful leader in decades, a delegation of very senior American technology and finance CEOs, including Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook, Tim Cook of Apple, and Stephen Schwarzman of the Blackstone private equity firm, were shown on national Chinese television applauding Xi at a reception in Beijing's Great Hall of the People. The message is clear: to raise human rights concerns, even to object to Chinese censorship or to its demands for technology transfers, carries the real risk of being excluded from the Chinese market, and very few American corporations can take that risk.

This new politeness to China also conspicuously marked the visit of President Trump to Beijing. But his failure publicly to reassert Western values at a time of an authoritarian revival comes with a cost. As the Economist put it: “It makes it easier for China to declare American style democracy passé, and more tempting for other countries to copy China's autocratic model.”

This is not to say that China faces no obstacles as the major power in the Authoritarian International. As many analysts have pointed out, it carries a huge burden of debt; it has plenty of domestic discontent; and several large and powerful nearby countries have a vital interest in containing its power.

Still, China is bound to be a major force in the world for the foreseeable future, one that will use its power, prestige, and diplomatic clout to advance notions of state power and control over individual freedoms and checks and balances. In this sense, China poses what well may be the sharpest and most enduring challenge to the liberal democracies and to their values.

“I honestly believe a dominant and more hegemonic China would make for more dictatorships around the world, because there would be less criticism of countries behaving like them,” Ratner said. “There will be more countries locking up dissidents and journalists because there would be a lack of pressure to do otherwise.”